Crustacean Trilemma: Agency, Generality, Risk

Over the last few years, I’ve found myself coming back to the same question when thinking about AI systems: what actually makes them dangerous in practice? I was specifically interested in environments with real infrastructure, real incentives, and real failure modes as it pertains to practical AI security leaders are faced with today.

While thinking through this problem in 2023-2024, during my time at Georgetown University, I wrote a short piece outlining what I called a trilemma between Generality, Agency, and Alignment (yes, I know we hackerfolk love these triangles). I shared it with peers to see whether the idea held up on its own and later shared it anonymously on LessWrong.org. The response was encouraging, but at the time, the framing was still largely theoretical.

Since then, my perspective has shifted largely due to hands-on work assessing real systems during security engagements at Sentry. The core intuition still holds, but one of the terms matters much less to practitioners than I originally thought. For security leaders, alignment only matters insofar as it creates risk.

This post revisits the original trilemma and reframes it through a security lens. My agents suggest we rename it to the Crustacean Trilemma, and I think I agree.

The original trilemma:

The trilemma describes a tension between three properties we increasingly want from AI systems:

Generality:

The intelligence to operate across many domains, tasks, and contexts. General systems are flexible, reusable, and intelligent across many tasks.

ANI (Low Generality) → AGI (High Generality)

Narrow AI Systems (ANI) are built to perform a limited set of tasks within well-defined boundaries (think OCR, chess-engines, AI in games) which makes their behavior easier to predict and constrain. As systems become more general (the road to AGI), they operate across broader contexts and inputs, increasing usefulness but also expanding the space of unexpected interactions and failure modes. Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) is a broader topic and out of scope for this article.

Agency:

The ability to act autonomously toward objectives. Planning, tool use, chaining actions, and operating with fewer humans in the loop.

Oracles (Low Agency) → Agents (High Agency)

Oracle systems (think chat interface with ChatGPT) respond to questions but do not act on the world directly. Their impact is mediated by a human decision-maker that applies its use in the real world. Agentic systems (think OpenClaw) go further by planning and executing actions on their own.

Alignment:

The degree to which system behavior remains consistent with human intent, values, and constraints even as context changes.

Misaligned (Failure Modes) → Aligned (Success Modes)

Alignment is a much discussed topic in the AI Sec/Safety space and has it’s own set of failure modes which are fascinating!

The Trilemma:

The intuition is simple: as systems become more general and more agentic, keeping them aligned becomes harder. Not because alignment is impossible, but because the space of possible behaviors expands faster than our ability to constrain it.

Where it becomes more interesting for security practitioners is when you drop it into real-world applications and production environments, where misalignment translates to risk.

From Theory to Practice

In cybersecurity, we rarely talk about alignment as a first-class concept. Alignment is a useful research concept, but it’s not how security leaders reason about exposure. We’re interested in risk as it pertains to controls, permissions, failure modes, and blast radius.

Concepts like:

- Introduction of new attack surfaces and vulnerabilities

- Systems operating correctly, but with limited oversight

- Automation trusted beyond its threat model

- Capabilities exposed without proportional governance

In other words, the failure modes for us practitioners are mundane, day-to-day things we deal with other traditional systems. Special Token Injection comes to mind.

Here’s a few examples in applying the crustacean trilemma:

Generality + Alignment ⇒ Agency curtailed.

One path to low-risk, aligned general systems is to curtail persistent agency. By confining a generally intelligent AI to provide information or predictions on request (like a highly advanced question-answering system or an LLM “chat” of possible responses) it is possible to leverage its broad knowledge while keeping it from executing plans autonomously. This setup encourages the AI to defer to human input rather than seize agency.

Modern large language models, which exhibit considerable generality, can be deployed as assistants with carefully constrained actions. They are aligned via techniques like instruction tuning and RLHF, but notably, these techniques limit the AI’s “will” to do anything outside the user’s query or the allowed policies. They operate in a text box, not roaming the internet autonomously (except with cautious tool-use, and always under user instruction). As a result, we get generally knowledgeable, helpful systems that lack independent agency – effectively sacrificing the agent property to maintain alignment.

Agency + Alignment ⇒ Limited Generality

The second combination to build low risk systems is using AI agents that are strongly aligned within a narrow domain or limited capability level. Narrow AI agents (a chess engine, a malware classifier, or autonomous vehicle) have specific goals and can act autonomously, but their generality is bounded. This limit on scope simplifies alignment: designers can more exhaustively specify objectives and safety constraints for a confined task environment.

Systems in many specialized roles (drones, industrial robots, recommendation algorithms) operate with agency but within narrow scopes and with heavy supervision or “tripwires” to stop errant behavior. For example, an autonomous driving system is designed with explicit safety rules and operates only in the driving context. It has agency (controls a vehicle) and is intended to be aligned with human safety values, but it certainly cannot write a novel or manipulate the stock market. In essence, we pay for alignment by constraining the AI’s generality.

Generality + Agency ⇒ Alignment sacrificed.

OpenClaw is an open-source autonomous AI assistant that runs on local hardware, integrates with messaging and productivity systems, and can execute workflows on behalf of users. This combination of broad capability across contexts and permission to act without human mediation introduces a significant amount of risk. Security researchers have identified many vulnerabilities and failure modes in the wild and controlled environments.

The extensible “skill” ecosystem has already produced hundreds of community extensions with critical vulnerabilities and malicious functionality, effectively turning intent into execution with real consequences. Because OpenClaw agents run with high privilege on hosts and can be hijacked via input and third-party code, the blast radius of even non-malicious misuse extends well past isolated misclassification into credential theft, supply-chain compromise, and execution-level control. These outcomes exemplify what happens when generality and agency are combined: risk expands greatly.

A simple risk checklist for agentic systems

When evaluating risk for an AI system in your organizations, start with two questions.

Is the system general?

Does it operate across multiple domains, data sources, or tasks, or is it confined to a narrow, well-understood problem space? How intelligent is it? The broader the context it can interpret, the more ambiguity it must resolve on its own.

Is the system agentic?

Can it take actions without human approval, chain decisions together, or affect systems beyond generating output?

From there, the risk profile becomes clearer.

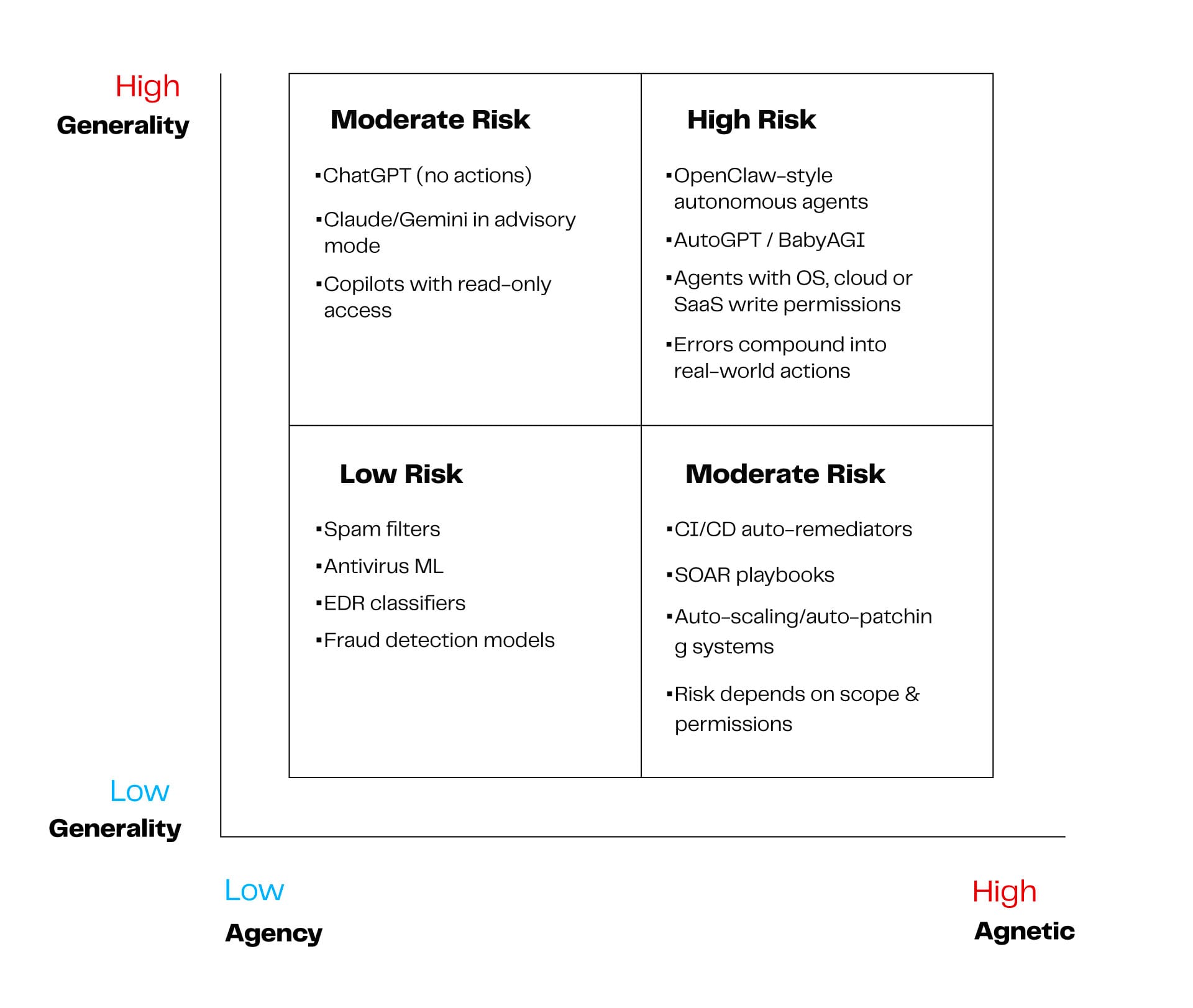

- Low generality, low agency: risk is marginal and failure modes are bounded. This is where spam filters and antivirus classifiers live.

- High generality, low agency: risk is manageable with oversight. These systems behave like oracles, powerful in analysis but constrained in execution. They are easier to govern with humans in the loop.

- Low generality, high agency: risk depends on scope discipline. Narrow autonomous systems can be safe if permissions, environments, and objectives are tightly constrained with good oversight.

- High generality, high agency: assume elevated risk by default. Broad context combined with autonomous action creates systems that introduce a combinatorial explosion of failure modes, and unless governance is explicitly engineered, the third vertex, risk, increases exponentially.

Let us know what's ur take?

As you’ve probably noticed, this piece is written from a personal perspective, and that’s because it was ideated, thought through, and written by Sentry Co-Founder Robert Shala.

It was originally written during his studies at Georgetown University, then shared anonymously on LessWrong and sent to his peers to see whether the idea could stand on its own.

Now, we’re officially publishing it as a blog piece for our dear Sentry audience.